Back in the year 2011, twenty years ago, four children lived on a magical island called Utila, which looked like a whale swimming in a blue-green sea.

Maxim, who was four,

and Pai, who was eight months old,

were brother and sister.

Bine, who was four years old,

and Angus, who was two,

were also brother and sister.

All four of these children were friends and played together all the time, except that Pai, being so young, couldn’t talk to her friends, because she couldn’t talk at all. Still, she was part of the charmed circle, or rather rectangle, that these children formed. One thing they had in common was that each of them possessed stunning beauty, as you see. They were also very smart and very nice, which some people think is even more important than being beautiful.

Maxim and Bine, who were the same age, had been friends their whole life. In fact, they loved each other, and it seemed natural to them that when they grew up, they would get married and have smart, nice, beautiful children of their own, although they didn’t yet know how to have children.

But when they started going to school, another girl fell in love with Maxim.

and that made Bine worried and sad. She worried that Maxim would fall out of love with her and in love with the other girl, and that they wouldn’t be able to get married after all.

Maxim didn’t worry about things like that because he knew that he was a prince and Bine was a princess, and that someday he would build a house for her. Besides, he was a boy, and boys don’t worry about things; they just want to get through the day.

But Bine need not have worried. Even though he and his parents and his sister moved away from the magical island to a country across the ocean, Maxim went on loving Bine. Over the years, many other girls fell in love with him because he had the longest eyelashes of any boy they knew. And many other boys fell in love with Bine’s blond hair and brown eyes. When other people fell in love with Maxim and Bine, they would sometimes forget each other for a little while, but then Bine would remember that it was Maxim she really loved, and Maxim would remember that it was Bine he really loved. And last year, in 2030, they got married on the beach of the magical island of Utila.

But what of Angus and Pai? Pai moved away from the island with her parents and Maxim before she and Angus could become close friends, and she only remembered him from pictures of him that her parents showed her. But he remembered her very well, because he had fallen in love with her way back when they were very little.

And when her whole family came back to the island for the wedding of Bine and Maxim, she looked at the handsome young man whom Angus had grown up to be, and fell in love with him. And Angus looked at the beautiful young woman whom Pai had grown up to be, and fell in love with her all over again. For the next year, even though Pai had gone back to America, where she was attending a school called the New York University, she and Angus texted and twittered and e-mailed and telepathed and mind-locked every day, so it was almost as if they were together, except that they couldn’t touch, or go swimming, or eat lunch with each other. But they knew each other so well that they wanted to spend their whole lives together, and one year to the day after Bine and Maxim had gotten married on the beach, Pai and Angus got married on the beach, at the same spot, near the house of Amanda and John, the mother and father of Bine and Angus.

And Danielle and Benoit, the parents of Maxim and Pai, came to both of these weddings.

and so did the old, doddering grandparents of the four now-grown-up children, and everybody ate gooey cake and drank bubbly champagne. And they all lived happily ever after.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Sunday, September 11, 2011

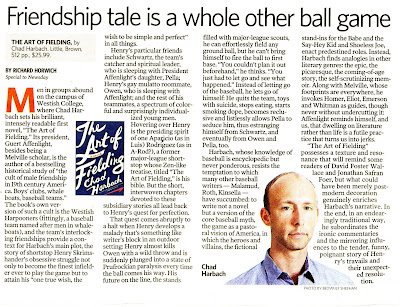

REVIEW OF "THE ART OF FIELDING," NEWSDAY, SEPT. 11, 2011

Men in groups abound on the campus of Westish College, where Chad Harbach sets his brilliant, intensely readable first novel, The Art of Fielding. Its president, Guert Afflenlight, besides being a Melville scholar, is the author of a best-selling historical study of what is described as “the cult of male friendship in nineteenth-century America . . . boys’ clubs, whale boats, baseball teams.” The book’s own version of such a cult is the Westish Harpooners (fittingly, a baseball team named after men in whale boats), and the team’s interlocking friendships provide a context for Harbach’s main plot, the story of shortstop Henry Skrimshander’s obsessive struggle not only to become the finest infielder ever to play the game but to attain his “one true wish, the wish to be simple and perfect” in all things.

Henry’s particular friends include Schwartz, the team’s catcher and spiritual leader, who is sleeping with President Affenlight’s daughter, Pella; Henry’s gay mulatto roommate Owen, who is sleeping with Affenlight himself; and the rest of his teammates, a spectrum of colorful and surprisingly individualized young men. Hovering over Henry is the presiding spirit of one Aparicio (as in Luis) Rodriguez (as in A-Rod?), a former major-league shortstop whose Zen-like treatise, meta-titled The Art of Fielding, is his bible, as Moby-Dick is Affenlight’s. But the short, interwoven chapters devoted to these subsidiary stories all lead back to Henry’s quest for perfection.

That quest comes abruptly to a halt when Henry (like several real-life ballplayers – Steve Blass, Steve Sax, Chuck Knoblauch) develops a malady that’s something like writer’s block in an outdoor setting: Henry almost kills Owen with a wild throw and is suddenly plunged into a state of Prufrockian paralysis every time the ball comes his way. His future on the line, the stands filled with major-league scouts, he can effortlessly field any ground ball but he can’t bring himself to fire the ball to the first base. “You couldn’t plan it out beforehand,” he thinks. “You just had to let it go and see what happened.” Instead of letting go of the baseball, he lets go of himself: he quits the team, toys with suicide, stops eating, starts smoking dope, becomes reclusive and listlessly allows Pella to seduce him, thus estranging himself from Schwartz, and eventually from Owen and Pella too.

Harbach, whose knowledge of baseball is encyclopedic but never ponderous, resists the temptation to which many other baseball writers – Malamud, Roth, Kinsella -- have sucumbed: to write not a novel but a version of the core baseball myth, the game as a pastoral vision of America, in which the heroes and villains, the fictional stand-ins for the Babe and the Say-Hey Kid and Shoeless Joe, enact predestined roles. Instead, Harbach finds analogies in other literary genres: the epic, the picaresque, the coming-of-age story, the self-scrutinizing memoir. Along with Melville, whose footprints are everywhere, he invokes Homer, Eliot, Emerson and Whitman as guides, though never without ironically undercutting this technique; Affenlight reminds himself, and us, that dwelling on literature rather than life is a futile practice that turns us into jerks.

The Art of Fielding posesses a texture and resonance that will remind some readers of David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Safran Foer, but what could have been merely post-modern decoration genuinely enriches Harbach’s narrative. In the end, in an endearingly traditonal way, he subordinates the ironic commentaries and the mirroring influences to the tender, funny, poignant story of Henry’s travails and their unexpected resolution.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

RULES OF THE ROAD

THE RIGHT (LEFT) SIDE

It makes me crazy, as I drive or bike around the East End, to see so many walkers, runners, strollers, moms/nannies pushing baby carriages, sometimes two or three abreast, on the right side of narrow shoulderless tree-lined and therefore shadowy roads – Stony Hill Road in East Hampton comes to mind -- which is the wrong side of the road for them. Their backs are to the traffic. Often they’re on their cells; if not, they’re listening to their iPods, as I bear down on them. Often it’s twilight. Often they’re wearing dark clothing. Come on, people! Don’t you want at least a fighting chance at surviving an encounter with a motorist who is blinded by the sun or the darkness or fiddling with his own phone or music player?

When I come up on a hapless pedestrian, though I know it stamps me instantly as a curmudgeon who is to be either ignored or given the finger, occasionally I can't resist the urge to slow down and try to reason with the 16-year-old girl or the portly middle-aged fellow inches from my right fender. “Safer to run facing traffic!” I’ll yell through my lowered passenger-side window. The other day when I did this, a woman pushing a stroller gave me a thoughtful look, said “Thanks,” and, I watched her cross to the left side in my rear-view mirror. I was so happy, I almost ran down a runner a hundred feet further on.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

INEXORABILITY

What's on my mind today is Fate. To be specific, the fate of a single, nondescript brown moth that landed its bedraggled self on the steaming tennis court whose bench a friend and I were sitting on between games. No sooner had the moth touched down than, as if in some infernal Rube Goldberg device, a tennis ball detached itself from a lesson being given two courts away and trundled, slowly but very straight, toward us and the moth. And as its momentum expired, it homed in on the fragile creature and with on its final turn, like some fuzzy juggernaut, ran over it. It was sheer coincidence, of course, but the vector was so precise that it felt like something else. What would the last thought of the moth, had it been sentient, have been? Something like, "Of all the gin joints in all the wor--"

Monday, August 1, 2011

ROMEO AND JULIET IN AFGHANISTAN

The Times headline read “Afghans Rage at Young Lovers; A Father Says Kill Them Both.”

The bare facts are these: two teenagers “of different ethnicities” –- Rafi (pictured above in his prison cell) is Tajik, Halima is Hazara (guaranteeing that a marriage between them would not have been arranged by their parents) -- tired of meeting in secret, obtained a car and eloped, heading for a courthouse where they intended to marry. They had driven only thirty feet when a group of men stopped them, pulled them into the road, and interrogated them: what right had they to appear in public together? “An angry crowd of 300 surged around them, calling them adulterers and demanding that they be stoned to death or hanged.”

Police arrived, and a riot ensued, in which one man was killed. The kids were spirited off to jail (undoubtdly the safest place for them), where they languish at present, awaiting trial. There is no indication that they had engaged in, or were engaged in, any activity more culpable or subversive than sitting companionably together in an automobile.

“Why can we not marry each other, or love each other?” the 17-year-old Halima asks, from her prison cell.

If this sounds familiar, perhaps its because the narrative’s outlines conform so perfectly to those of Romeo and Juliet. That is, depending on how it ends, we might well have cause to describe this story as a tragedy. Except that, in Shakespeare’s play, only two characters display anything like the fanaticism that seems to characterize the Afghan social milieu -- Juliet’s hot-headed Tybalt (who indeed thinks Romeo should be put to death, by himself) and Juliet’s father, in a single scene in which he loses his temper volcanically. The deaths of the young protagonists come about because of a series of miscalculations and fatal coincidences: Romeo kills himself because he believes Juliet dead when she is in fact living, and Juliet kills herself when the Friar, who is by her side in the family mausoleum, is spooked and runs away. The parents, at the plays end, mourn their children and erect statues in memory of them.

But in the present case, the girl’s uncle visited her in prison to inform her that she had shamed the family, and that they would kill her once she was released. Her father stated, “What we would ask is that the government should kill both of them,”

What’s happening in Afghanistan seems to me less than tragic and worse than tragic. Tragedies are about heroic attempts to defeat overwhelming odds, in which the dignity and seriousness of the hero’s (or heroes’) downfall produces in us a complicated blend of admiration, sadness, and resignation. I don’t know about you, but all I can feel about this is rage and a sense that human culture and the bonds of family as we know them have somehow been suspended. There’s no dignity, no heroism, no sense of individual fate playing itself out. Two children are about to be crushed by an ideologically-driven machine, and there seems to be no way of stopping it. (Of course, the law is always a machine, blind and capable only of quantitative judgments; that’s why Cocteau titled is version of the Oedipus story La machine infernelle.) The genre that fits here is not tragedy but irony, whose point of view is such that it reduces human life to a meaningless shadow-play. Macbeth described human life as a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing. The lives of Rafi and Halima, in their culture, apparently signify nothing. It’s not a tale told by an idiot; it’s a tale about idiots.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

MINIMALIST THEATER

As You Like It, the Public Theater, 2003

My last blog expressed my admiration for the Green Theatre Collective and their approach to performing theater. The “Green” in their title is not someone’s name; it’s part of their mission to make theatrical production environmentally friendly, to use up as few unsustainable resources as they can. This means taking a “minimalist” approach to theater, the most radical feature of which is: no stage. When Peter Quince, the director of Pyramis and Thisbe the play nestled nestled inside A Midsummer Night’s Dream) takes his band of rude mechanicals into the woods in search of a place to rehearse, he finds just the spot: “This green plot shall be our stage,” he tells them. There’s a metadramatic joke here, of course; the original audience had been watching the actors perform on a stage which they were forced to imagine as a wood; now, either they had to reimagine it as a stage, or simply stop imagining it altogether. The joke is lost, of course, if the stage has been transformed with fake grass and trees into a forest. GTC goes one step further: they perform the whole play on an actual green plot -- in the case of last week’s As You Like It, a lawn on a farm in Shelter Island.

They also employ no sets, no artificial light, vestigial costumes, and only seven actors for a play whose Dramatis Personae specifies 26 speaking parts. This may be, for them, largely a political and practical decision: they’re saving the earth and making do with what resources they can muster. I experience it more in esthetic terms. I’m a minimalist at heart; I hate lavishness. When I was 19, I saw Aida performed at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome with more pomp and circumstance than Kate and William’s wedding; there were live elephants on stage. I hated it. I was bored by the recent Tony-winning play War Horse, which as far as I was concerned was all chrome and no motor.

To make the overcoming of obstacles the dynamic of performing a play is not a new idea. Shakespeare would no doubt have welcomed kleig lights, rear projection, moveable sets and recorded sound effects, but he not only made do without them, he made the lack of them work for him. In the Prologue to Henry V, the Chorus disingenuously proclaims both the inadequacy of the project and its solution:

But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraised spirits that have dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object: can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this great accompt,

On your imaginary forces work.

Shakespeare and Company, in the Berkshires, specializes in small-cast Shakespeare; I saw them do Julius Caesar with five actors, and tour-de-force of doubling. And the Public Theater, in 2003, 21-year-old Bryce Dallas Howard and six even lesser-known actors did an amazing As You Like It, in which most of the problems were solved by tumbling and acrobatics: Ron Pisoni played both Orlando and his brother Oliver, and in a dialogue between them, switched characters by doing alternate back and forward somersaults, donning and doffing a hat in midair.

Movies, television and the modern theater can supply whatever is needed in the way of realism without taxing the audience's willing suspension of disbelief; in fact, that's the business that Pixar is in. The Dogma movement in film, which I find ridiculously rigid and tendentious in most respects, is at least an attempt to clear the clutter. But thank God for underfunded but undiscouraged theater companies that are proving, all over the world, that less is much more than more.

Tomorrow or the next day: minimalism in text.

My last blog expressed my admiration for the Green Theatre Collective and their approach to performing theater. The “Green” in their title is not someone’s name; it’s part of their mission to make theatrical production environmentally friendly, to use up as few unsustainable resources as they can. This means taking a “minimalist” approach to theater, the most radical feature of which is: no stage. When Peter Quince, the director of Pyramis and Thisbe the play nestled nestled inside A Midsummer Night’s Dream) takes his band of rude mechanicals into the woods in search of a place to rehearse, he finds just the spot: “This green plot shall be our stage,” he tells them. There’s a metadramatic joke here, of course; the original audience had been watching the actors perform on a stage which they were forced to imagine as a wood; now, either they had to reimagine it as a stage, or simply stop imagining it altogether. The joke is lost, of course, if the stage has been transformed with fake grass and trees into a forest. GTC goes one step further: they perform the whole play on an actual green plot -- in the case of last week’s As You Like It, a lawn on a farm in Shelter Island.

They also employ no sets, no artificial light, vestigial costumes, and only seven actors for a play whose Dramatis Personae specifies 26 speaking parts. This may be, for them, largely a political and practical decision: they’re saving the earth and making do with what resources they can muster. I experience it more in esthetic terms. I’m a minimalist at heart; I hate lavishness. When I was 19, I saw Aida performed at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome with more pomp and circumstance than Kate and William’s wedding; there were live elephants on stage. I hated it. I was bored by the recent Tony-winning play War Horse, which as far as I was concerned was all chrome and no motor.

To make the overcoming of obstacles the dynamic of performing a play is not a new idea. Shakespeare would no doubt have welcomed kleig lights, rear projection, moveable sets and recorded sound effects, but he not only made do without them, he made the lack of them work for him. In the Prologue to Henry V, the Chorus disingenuously proclaims both the inadequacy of the project and its solution:

But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraised spirits that have dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object: can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this great accompt,

On your imaginary forces work.

Shakespeare and Company, in the Berkshires, specializes in small-cast Shakespeare; I saw them do Julius Caesar with five actors, and tour-de-force of doubling. And the Public Theater, in 2003, 21-year-old Bryce Dallas Howard and six even lesser-known actors did an amazing As You Like It, in which most of the problems were solved by tumbling and acrobatics: Ron Pisoni played both Orlando and his brother Oliver, and in a dialogue between them, switched characters by doing alternate back and forward somersaults, donning and doffing a hat in midair.

Movies, television and the modern theater can supply whatever is needed in the way of realism without taxing the audience's willing suspension of disbelief; in fact, that's the business that Pixar is in. The Dogma movement in film, which I find ridiculously rigid and tendentious in most respects, is at least an attempt to clear the clutter. But thank God for underfunded but undiscouraged theater companies that are proving, all over the world, that less is much more than more.

Tomorrow or the next day: minimalism in text.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

SHAKESPEARE LIVES ON SHELTER ISLAND

First there was Hamptons Shakespeare Festival, in Montauk, for whom I worked as dramaturg for the six best summers of my life -- As You Like It, Twelfth Night, The Tempest, Much Ado About Nothing, The Winter's Tale, The Taming of the Shrew -- and which David Brandenburg has been trying to revive, so far without success. Then, when Josh Gladstone became the director of the John Drew Theater at Guild Hall, I was able to work on Julius Caesar, Macbeth and Hamlet. The two experiences were very different: one outdoors and the other indoors, one all romantic comedies and the other the darkest tragedies. But in two ways they were alike: they exhibited artistry in the highest degree, and they lost money. So, for the past five years, there's been no Shakespeare east of Shinnecock -- no Bard in Bridgehampton, no Avon in Amagansett, no William in Wainscott, no . . . well, you get the idea.

So I've pined, and languished, and made occasional summer forays into New York to keep my Shakespeare jones mamageable. But this past weekend, as if in some kind of time warp, Shakespeare came back to me. A company called the Green Theatre Collective, very young, enthusiastic and talented, has been roaming the Northeast, performing for a night or two in unlikely venues. What makes their work eco-theatrical is their tiny footprint: they don't build sets, they don't use artificial lighting (and so perform at 5 PM), they wear street clothes, and there are very few of them: on Sunday, we watched seven talented actors bring As You Like It to life at Sylvester Manor, essentially a working farm with some cultural ambitions on Shelter Island, with only an sail-less windmill as a backdrop.

Part of the process of paring down involved cutting the text and doubling most of the parts, which is part of the fun: the aristocratic Rosalind was equally convincing both as the male Ganymede and as the sluttish Audrey, and the fearsome Charles the Wrestler, at court, morphed into a gentle elderly peasant in the Forest. Sarah Hankins, the director, deserves full credit for making the limitations into benefits. She omitted Jaques's tedious and unnecessary farewell speech at the end; instead, the audience's peripheral vision caught the melancholy fellow ambling sadly away from the festivities on stage, a sad and moving moment.

I talked to the company's executive director, Hal Fickett (who played Orlando; everyone wears several hats) about the logistics of the operation. In a way, it's very simple: like their itinerant sixteenth-century forbears, they roam the countryside, accepting what humble food and lodging they can promote, living by their wits and Shakespeare's. They're living proof that large ensembles, expensive machinery, and modern technology are almost beside the point. There's an argument in the last act of A Midsummer Night's Dream in which Theseus, defending the efforts of the amateurs who are presenting a play so tragic it's funny, so bad it's wonderful, by saying, about plays in general, "The best in this kind are but shadows, and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them." His bride Hippolyta replies, "It must be your imagination then, and not theirs," and she's hit the bullseye: the more imaginative work the audience has to do, the more rewarding their experience will be. Lope de Vega, the great Spanish contemporary of Shakespeare's, described theater as merely "two boards and a passion," but as the Green Theatre Collective is proving, you don't even need boards if you have enough passion.

The company's website is http://www.greentheatrecollective.org/.

So I've pined, and languished, and made occasional summer forays into New York to keep my Shakespeare jones mamageable. But this past weekend, as if in some kind of time warp, Shakespeare came back to me. A company called the Green Theatre Collective, very young, enthusiastic and talented, has been roaming the Northeast, performing for a night or two in unlikely venues. What makes their work eco-theatrical is their tiny footprint: they don't build sets, they don't use artificial lighting (and so perform at 5 PM), they wear street clothes, and there are very few of them: on Sunday, we watched seven talented actors bring As You Like It to life at Sylvester Manor, essentially a working farm with some cultural ambitions on Shelter Island, with only an sail-less windmill as a backdrop.

Part of the process of paring down involved cutting the text and doubling most of the parts, which is part of the fun: the aristocratic Rosalind was equally convincing both as the male Ganymede and as the sluttish Audrey, and the fearsome Charles the Wrestler, at court, morphed into a gentle elderly peasant in the Forest. Sarah Hankins, the director, deserves full credit for making the limitations into benefits. She omitted Jaques's tedious and unnecessary farewell speech at the end; instead, the audience's peripheral vision caught the melancholy fellow ambling sadly away from the festivities on stage, a sad and moving moment.

I talked to the company's executive director, Hal Fickett (who played Orlando; everyone wears several hats) about the logistics of the operation. In a way, it's very simple: like their itinerant sixteenth-century forbears, they roam the countryside, accepting what humble food and lodging they can promote, living by their wits and Shakespeare's. They're living proof that large ensembles, expensive machinery, and modern technology are almost beside the point. There's an argument in the last act of A Midsummer Night's Dream in which Theseus, defending the efforts of the amateurs who are presenting a play so tragic it's funny, so bad it's wonderful, by saying, about plays in general, "The best in this kind are but shadows, and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them." His bride Hippolyta replies, "It must be your imagination then, and not theirs," and she's hit the bullseye: the more imaginative work the audience has to do, the more rewarding their experience will be. Lope de Vega, the great Spanish contemporary of Shakespeare's, described theater as merely "two boards and a passion," but as the Green Theatre Collective is proving, you don't even need boards if you have enough passion.

The company's website is http://www.greentheatrecollective.org/.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

DOPPELGANGERS?

He did it! Well, of course he did; it was only a matter of time. Some record-breaking performances are exciting because the question is whether the record will indeed be broken. Will someone on the PGA tour shoot a 58? Did Roger Maris hit 61 home runs, breaking Ruth’s season record, but in 8 more games? But it wasn’t a question of if Derek Jeter would get his 3000th hit but only when – and, given the season he’s been having, I dreaded the wait, the countdown. Remember when A-Rod was trying to hit that 600th home run, and kept not doing it? Get it over with, already.

As it turned out, in Jeter’s case, the wait was worth it. For a basically shy, closed-in, inarticulate person, judging from interviews, he has always had a flair for the dramatic: the “Flip Play” against Oakland in 2001, the catch he made against Boston diving into the stands and emerging with the ball and facial bruises are only two of the most famous examples. But five hits, the 3000th a shot into the left-field stands, the 3003rd a game-winning single!

But what makes him my favorite ballplayer, and the role model, the icon, the poster boy for the Great American Pastime, is not his operatic moments but what has come to be called his “work ethic”: no one in the game prepares more diligently and gives more of himself. In an age when great players like Manny Ramirez and Miguel Tejada (to name two egregious defenders) are known for loafing down to first after they’ve hit a ground ball to an infielder or are sure they’ve hit a home run, Jeter runs everything out. Maybe the infielder sees you busting down the line and makes a bad throw. Maybe your home run doesn’t quite make it and caroms off the wall and you end up at 2nd or even 3rd. When Jeter homered historically on July 9th, he put his head down and sprinted for first, and he didn’t slow to a jog until he’d rounded the bag, at which point the Rays’s first baseman literally took his hat off to him.

There was another, older ballplayer known for Jeter’s type of play, so much so that his nickname was “Charlie Hustle.” His real name was Pete Rose, but he might as well be called the Antichrist, if you judge him as organized baseball does. On and off the field, he was the antithesis of Jeter, a pugnacious wise guy who played rough (he broke a catcher’s shoulder in the All-Star Game by slamming into him at the plate) and bullied umpires; he was indicted for tax evasion; he was twice-divorced, the second time on uncontested grounds of adultery -- and he liked to gamble, which was his fatal weakness. After an amazing 22-year career as a player he became the manager of the Reds, the team he had played for. In 1989 he was accuseed of betting on them and permanently barred from baseball. That meant barred from the Hall of Fame, as well. Of course, betting against his team would have been a mortal sin, since, as manager, he could have easily rigged games by adjusting the line-up. But even betting that the Reds would win was unsavory – a sportswriter claimed that he never placed bets on nights when he named Mario Soto or Bill Gullickson as his starters.

Rose denied the charges until, in 2004, he wrote an autobiography in which he confessed to this sin. This only seemed to enrage the powers that be even more; he was accused of hypocrisy for waiting 15 years before coming clean. During those years, he lived a sqaulid life, even, at one point, sinking to professional wrestling.

Jeter’s accomplishment is not to be scoffed at. It takes talent consistently displayed over many years to amass 3,000 base hits. Only 26 other players have done it, and none of them Yankees – not Gehrig, not Ruth, not Mantle. The 3,000 hit club is one of the most exclusive in sports. Jeter will be a first-ballot unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame when he retires, and he deserves to be, not least because of all those base knocks.

But what bothers me is that the moment after they put the bat on the ball, Derek Jeter and Charlie Hustle looked a lot alike. If Jeter’s accomplishments on the field deserve to be celebrated both as athletic feats and paradigms of ethical behavior, how are Rose’s great moments invalidated by his private failings? What happens if we judge them both simply as ballplayers? Know how many hits Pete Rose, the Other, the Unmentionable, the living repudiation of all that baseball would like itself to be, ended up with? Four thousand, two hundred and sixty-five.

As it turned out, in Jeter’s case, the wait was worth it. For a basically shy, closed-in, inarticulate person, judging from interviews, he has always had a flair for the dramatic: the “Flip Play” against Oakland in 2001, the catch he made against Boston diving into the stands and emerging with the ball and facial bruises are only two of the most famous examples. But five hits, the 3000th a shot into the left-field stands, the 3003rd a game-winning single!

But what makes him my favorite ballplayer, and the role model, the icon, the poster boy for the Great American Pastime, is not his operatic moments but what has come to be called his “work ethic”: no one in the game prepares more diligently and gives more of himself. In an age when great players like Manny Ramirez and Miguel Tejada (to name two egregious defenders) are known for loafing down to first after they’ve hit a ground ball to an infielder or are sure they’ve hit a home run, Jeter runs everything out. Maybe the infielder sees you busting down the line and makes a bad throw. Maybe your home run doesn’t quite make it and caroms off the wall and you end up at 2nd or even 3rd. When Jeter homered historically on July 9th, he put his head down and sprinted for first, and he didn’t slow to a jog until he’d rounded the bag, at which point the Rays’s first baseman literally took his hat off to him.

There was another, older ballplayer known for Jeter’s type of play, so much so that his nickname was “Charlie Hustle.” His real name was Pete Rose, but he might as well be called the Antichrist, if you judge him as organized baseball does. On and off the field, he was the antithesis of Jeter, a pugnacious wise guy who played rough (he broke a catcher’s shoulder in the All-Star Game by slamming into him at the plate) and bullied umpires; he was indicted for tax evasion; he was twice-divorced, the second time on uncontested grounds of adultery -- and he liked to gamble, which was his fatal weakness. After an amazing 22-year career as a player he became the manager of the Reds, the team he had played for. In 1989 he was accuseed of betting on them and permanently barred from baseball. That meant barred from the Hall of Fame, as well. Of course, betting against his team would have been a mortal sin, since, as manager, he could have easily rigged games by adjusting the line-up. But even betting that the Reds would win was unsavory – a sportswriter claimed that he never placed bets on nights when he named Mario Soto or Bill Gullickson as his starters.

Rose denied the charges until, in 2004, he wrote an autobiography in which he confessed to this sin. This only seemed to enrage the powers that be even more; he was accused of hypocrisy for waiting 15 years before coming clean. During those years, he lived a sqaulid life, even, at one point, sinking to professional wrestling.

Jeter’s accomplishment is not to be scoffed at. It takes talent consistently displayed over many years to amass 3,000 base hits. Only 26 other players have done it, and none of them Yankees – not Gehrig, not Ruth, not Mantle. The 3,000 hit club is one of the most exclusive in sports. Jeter will be a first-ballot unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame when he retires, and he deserves to be, not least because of all those base knocks.

But what bothers me is that the moment after they put the bat on the ball, Derek Jeter and Charlie Hustle looked a lot alike. If Jeter’s accomplishments on the field deserve to be celebrated both as athletic feats and paradigms of ethical behavior, how are Rose’s great moments invalidated by his private failings? What happens if we judge them both simply as ballplayers? Know how many hits Pete Rose, the Other, the Unmentionable, the living repudiation of all that baseball would like itself to be, ended up with? Four thousand, two hundred and sixty-five.

Saturday, July 9, 2011

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY

Age starts to catch up with almost everyone in their 40's, especially with their vision. You find yourself holding the menu farther and farther away, or squinting with one eye to make out blurry letters and figures, until you give in and buy a pair of reading glasses to correct your advancing far-sightedness.

Since the whole population is aging, you'd think the people who design our products would be cognizant of this problem, but they're not -- largely, I think, because engineering is a young person's game. This is certainly true in the software business; those 23-year-old whiz-bangs don't think like the rest of us or see like the rest of us, which is why digital cameras, for example, come loaded with sub-sub-menus that are incomprehensible to laymen. I'd include a picture of mine if I could figure out how to point the front of the camera at the back of the camera, but you get the idea. At least the viewfinder has a diopter adjustment, so I can focus on what I'm focusing on. My wife's camera, which is newer, does away with the viewfinder altogether (people prefer, or are believed to prefer, screens, which suck power out of the battery like a weasel sucking eggs), and to use it, I have to don, of course, my reading glasses.

But let's stick with the vision thing. Above are two control panels, the top one from our brand-new Hamilton Beach toaster oven, the bottom one the detachable face of our after-market Miata AM-FM-CD player. Note the size of the words and numbers on the toaster oven, and their placement on the dials. Not only do I have to put on my specs to operate them, I have to stoop down until I'm on the same level as the thing, because otherwise the bottom portion of the temperature range (top dial) and the length of desired cooking time (bottom dial) are hidden from view.

As to the sound system, I think it speaks for itself. There are no fewer than 24 controls on the thing, most of them rocker switches with teensy-weensy numbers on them for mode, preset stations, and a host of other functions. At 60 miles per hour, do you really want to be crouching to peer down at your radio, trying to remember where the volume control is or what you have to press to skip a track on a CD?

I could multiply these examples by a hundred; these happened to be handy. There are exceptions. Thank you, Kindle, for letting me choose the type size of whatever I'm reading. And thank you iPad for letting me enlarge any portion of the screen just by pinching it. But I wouldn't accept an iPhone if you gave me one, and my iPod isn't much better.

By the way: if you're having trouble making out the details on the pictures above, you're proving my case.

Saturday, July 2, 2011

JEFF NUNOKAWA AND THE FACEBOOK CONFESSIONAL

Jeff Nunokawa

I’ve written two books in my life – my dissertation (which was carved up and published as four articles) in 1967, and Shakespeare’s Dilemmas, which was published in 1988 and got me promoted to full professor at Brooklyn College. Both were worthwhile projects; both were endless torture. I’m not suited to the format; I can’t hold the whole thing in my mind at one time. My late friend Richard Uviller was exasperated by my failure to write more books; he thought I had much to say, he admired my writing, he told me I was denying my destiny. Not so, I kept telling him. My destiny, in literary terms at least, takes a short-format form: I write articles.

He refused to accept that explanation: articles, even scholarly ones, are ephemera, he claimed – they exist only for a moment, and are then buried under an avalanche of more articles. Did Shakespeare write articles, he would ask?

Well, no, but Shakespeare wrote sonnets, and if I were a serious poet, so would I. I think the greatest poem written in English is Paradise Lost, which is ten thousand lines long, but of course the epic form is not for me. Fourteen lines seeems about right. Wordsworth wrote a sonnet that defended sonnets from the charge that they were too slight to matter; it begins,

Scorn not the sonnet: Critic, you have frown’d,

Mindless of its just honours; with this key

Shakespeare unlock’d his heart; the melody

Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch’s wound. . . .

The image of unlocking the heart points to the private, confessional nature of the sonnet; sonnets were sometimes writ small and folded into lockets, shown at the writer’s whim to whoever was deemed worthy. No less a personage than Elizabeth I indulged in this practice. I’m not a poet, though I write occasional verse, for birthday, wedding and anniversary toasts (see my birthday toast to Roger Sherman in the previous blog), but I can’t resist reprinting a poem I wrote while stuck in a subway tunnel one day years ago:

They have no need of poetry,

Those who should be moving shortly in the sooty tubes

Beneath the river that surfaces at Times Square.

No need of Strand's or Clampitt’s airy overviews

That fresco the walls of buses,

Short-haul limos awash in the city’s changing lights.

No, those with tunnel vision

Have more pressing concerns

Than thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird.

They need to know

Where to get their torn earlobes stitched

How to avoid AIDS and its evil twin SIDA

And most of all

What steps to take

When they can’t move

And the lights go out.

But I’ve never followed up with more verse. If I did, it would probably be haiku; for me, as for Shakespeare and Wordsworth, the thrill of the short poem is the tension between getting something said despite the formal obstacles – in the latter case, 17 syllables, arranged in a 5-7-5 three-line pattern. Haiku can be sensuous and lyrical, or funny:

Left the door open

For the prophet Elijah –

Now our cat is gone. (from Haiku for Jews)

Technology is on my side, of course. Twitter mandates a limit of 140 words; most internet writing is stripped bare of grammar, punctuation and prolixity. (Not mine; I write in standard English and proofread every e-mail I send.)

But I just read a Talk of the Town piece in the July 4th New Yorker that opened a door for me. There’s a professor at Princeton named Jeff Nunowaka who writes a Facebook note every day – the count now exceeds 3000. Typically they begin with a short citation from one of his favorite authors – George Eliot, Oscar Wilde, Gerard Manley Hopkins -- followed by scholarly “meditations – half literary-critical, half confessional.”

Nunowaka has respectable conventional credentials; he’s published two books, one on Dickens and Eliot and the other on Wilde. But he now prefers the sociability of Facebook, and the fact that he can more easily connect with undergraduates there. When I read about his approach, I felt instantly empowered. I’ll never write another book or journal article, and the book and play reviews that have occupied me for the past few years do feel insubstantial; when I fritter an afternoon away on the golf course, I feel guilty. I’m very bad about contributing to this blog, because very few people read it (though it’s an endless loop: I don’t write because they don’t read, and they don’t read because I don’t write). But Facebook as a viable medium for actual writing! Nunowaka and I are already “friends”; I’m going to ask him if it’s all right to start contributing notes to my own page.

He refused to accept that explanation: articles, even scholarly ones, are ephemera, he claimed – they exist only for a moment, and are then buried under an avalanche of more articles. Did Shakespeare write articles, he would ask?

Well, no, but Shakespeare wrote sonnets, and if I were a serious poet, so would I. I think the greatest poem written in English is Paradise Lost, which is ten thousand lines long, but of course the epic form is not for me. Fourteen lines seeems about right. Wordsworth wrote a sonnet that defended sonnets from the charge that they were too slight to matter; it begins,

Scorn not the sonnet: Critic, you have frown’d,

Mindless of its just honours; with this key

Shakespeare unlock’d his heart; the melody

Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch’s wound. . . .

The image of unlocking the heart points to the private, confessional nature of the sonnet; sonnets were sometimes writ small and folded into lockets, shown at the writer’s whim to whoever was deemed worthy. No less a personage than Elizabeth I indulged in this practice. I’m not a poet, though I write occasional verse, for birthday, wedding and anniversary toasts (see my birthday toast to Roger Sherman in the previous blog), but I can’t resist reprinting a poem I wrote while stuck in a subway tunnel one day years ago:

They have no need of poetry,

Those who should be moving shortly in the sooty tubes

Beneath the river that surfaces at Times Square.

No need of Strand's or Clampitt’s airy overviews

That fresco the walls of buses,

Short-haul limos awash in the city’s changing lights.

No, those with tunnel vision

Have more pressing concerns

Than thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird.

They need to know

Where to get their torn earlobes stitched

How to avoid AIDS and its evil twin SIDA

And most of all

What steps to take

When they can’t move

And the lights go out.

But I’ve never followed up with more verse. If I did, it would probably be haiku; for me, as for Shakespeare and Wordsworth, the thrill of the short poem is the tension between getting something said despite the formal obstacles – in the latter case, 17 syllables, arranged in a 5-7-5 three-line pattern. Haiku can be sensuous and lyrical, or funny:

Left the door open

For the prophet Elijah –

Now our cat is gone. (from Haiku for Jews)

Technology is on my side, of course. Twitter mandates a limit of 140 words; most internet writing is stripped bare of grammar, punctuation and prolixity. (Not mine; I write in standard English and proofread every e-mail I send.)

But I just read a Talk of the Town piece in the July 4th New Yorker that opened a door for me. There’s a professor at Princeton named Jeff Nunowaka who writes a Facebook note every day – the count now exceeds 3000. Typically they begin with a short citation from one of his favorite authors – George Eliot, Oscar Wilde, Gerard Manley Hopkins -- followed by scholarly “meditations – half literary-critical, half confessional.”

Nunowaka has respectable conventional credentials; he’s published two books, one on Dickens and Eliot and the other on Wilde. But he now prefers the sociability of Facebook, and the fact that he can more easily connect with undergraduates there. When I read about his approach, I felt instantly empowered. I’ll never write another book or journal article, and the book and play reviews that have occupied me for the past few years do feel insubstantial; when I fritter an afternoon away on the golf course, I feel guilty. I’m very bad about contributing to this blog, because very few people read it (though it’s an endless loop: I don’t write because they don’t read, and they don’t read because I don’t write). But Facebook as a viable medium for actual writing! Nunowaka and I are already “friends”; I’m going to ask him if it’s all right to start contributing notes to my own page.

ON ROGER SHERMAN'S BIRTHDAY

Well, our friend Roger, now you know

Firsthand the infamous Six-Oh.

It wasn't hard to get there, was it?

It doesn't feel that different, does it?

The only thing to fear is fear;

You're still the man you were last year.

And there are upsides to this fate:

You get the senior movie rate,

And modern medicine can aid

Those needing help to make the grade –

Prostheses come in every shape,

Supports for back, wrist, shoulder, nape.

Viagra, Rogaine, other pills

Now minister to many ills

That earlier were thought to be

The lot of oldsters such as we.

So buck up, Dude! Stiff upper lip!

If need be, go replace a hip!

A birthday's an excuse to party,

So let us drink a toast most hearty

To wisdom and accomplishment,

The films that help to pay the rent:

There’s danny meyer, Richard Rodgers,

Fast Eddie and his boyish codgers,

There’s calder and there’s chevrolet,

Plus more than we have time to say,

And one that hasn’t yet been seen:

an ode to israel’s cuisine.

To all the blessings that have flowed,

And to the fun that you’re still owed,

From those of us in the same fix,

Here's to another decades six!

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

NAME-DROPPING

BUTLER LIBRARY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

The above photo depicts a building that personifies, for me, the seven miserable and all-but-wasted years I spent as a graduate student at Columbia – the aloofness, the indifference, the elitism, the self-satisfaction of an institution that seemingly went out of its way to frustrate, depress and impoverish me and my classmates (with the exception of those who had graduated from Columbia College, who got all the grants and TA jobs). Yes, I got a doctorate. Everything I learned, I taught myself.

But I digress. What I want to point out is something the low-res photo doesn’t clearly show: the frieze of names that runs around all four sides of the structure, just above the columns. That’s right, names. Apparently, Nicholas Murray Butler, past president of the university and the man for whom the library is named, thought it would be appropriate to proclaim the university’s intellectual stance by featuring 18 dead white European males as a kind of proclamation: this is who we are, this what we stand for:

HOMER HERODOTUS SOPHOCLES PLATO ARISTOTLE DEMOSTHENES CICERO VERGIL [sic] HORACE TACITUS ST. AUGUSTINE ST. THOMAS AQUINAS CERVANTES DANTE SHAKESPEARE MILTON VOLTAIRE GOETHE

The choices, I suppose, are predictable. One might question the inclusion of Herodotus, Demosthenes, and Tacitus on the grounds of relevance and popularity, but it’s pretty much a syllabus of Columbia’s Core Curriculum, everything that the decanonization movement despised. No women, no non-Westerners, no persons of color (well, a case has been made that St. Augustine was the exception to both of the previous categories), only one candidate chosen from the last four centuries of human intellectual endeavor. But what interests me more than who is up there is the endeavor itself: to simply list their names. There's an incantatory feeling about it; you don’t have to read or study what they wrote, just recite the iconic monikers, and you've been somehow Improved.

Interestingly, the 92nd Street Y adopted the same approach when it decorated the Kauffman Concert Hall, which dates from the same period (1930), with a similar frieze:

SHAKESPEARE DANTE ISAIAH JEFFERSON WASHINGTON DAVID MOSES

BEETHOVEN LINCOLN MAIMONIDES

BEETHOVEN LINCOLN MAIMONIDES

The differences are more compelling than the overlap. It's as if this upstart institution, founded by upwardly-mobile Jews in a then unfashionable part of the city, felt compelled to demonstrate its twin loyalties: Hebraic tradition and lore are coupled with a declaration of loyalty to the history of the country that took them in. The grandchildren of Emma Lazarus’s “wretched refuse of [Europe’s] teeming shore” had gained a cultural foothold, and were acknowledging their debt to its hosts, even as they asserted the equality of its own tradition. Shakespeare, Dante and Beethoven are just filler -- default cultural markers, as it were.

But again, a kind of magic is at work, just as it is on 116th Street: the sheer power of the names itself is presumed to do part of the work that is usually ascribed to rigorous thought and study . It will improve us merely to saunter across campus or take a seat in the auditorium; we don’t actually have to enter the library or listen to a concert to be uplifted by Tradition.

Ben Jonson, in his wonderful play Epicoene, features a pompous fool named Sir John Daw (= jackdaw, a clamorous bird) who takes the same approach to learning:

CLERIMONT: What do you think of the poets, sir John?

DAW: Not worthy to be named for authors. Homer, an old tedious,

prolix ass, talks of curriers, and chines of beef. Virgil of

dunging of land, and bees. Horace, of I know not what.

CLERIMONT: I think so.

DAW: And so Pindarus, Lycophron, Anacreon, Catullus, Seneca the

tragedian, Lucan, Propertius, Tibullus, Martial, Juvenal,

Ausonius, Statius, Politian, Valerius Flaccus, and the rest--

CLERIMONT: What a sack full of their names he has got!

DAUPHINE: And how he pours them out!

DAW: Not worthy to be named for authors. Homer, an old tedious,

prolix ass, talks of curriers, and chines of beef. Virgil of

dunging of land, and bees. Horace, of I know not what.

CLERIMONT: I think so.

DAW: And so Pindarus, Lycophron, Anacreon, Catullus, Seneca the

tragedian, Lucan, Propertius, Tibullus, Martial, Juvenal,

Ausonius, Statius, Politian, Valerius Flaccus, and the rest--

CLERIMONT: What a sack full of their names he has got!

DAUPHINE: And how he pours them out!

Jonson’s name appears neither on Butler or at Kauffman. Wonder why?

Friday, March 4, 2011

CARRISHKEIT

I need to buy a new car -- or do I? Our 2003 VW Passat, the best car we've ever owned, has 117,000 miles on it, and things are going wrong: mysterious warning lights on the dash, like "Check Brake Pads," which the dealer's service department told us had appeared not because our brake pads were faulty, but only because they weren't made by VW, and, more alarmingly, "Check Engine," which usually means that the catalytic converter is failing and that the car won't pass inspection unless we spend thousands of dollars fixing it.

And yet . . . it runs like a dream. It's totally comfortable; in fact, I bought it because its driver's seat had so many possible configurations that I no longer have to stop, get out and stretch after an hour at the wheel. It has all-wheel drive, a necessity in the winter for our long, steep driveway, but it still gets 26 mpg on the highway, and its 6-cylinder engine, coupled to an automatic transition with manual passing gear, is smooth, quiet and powerful. And I love its bells and whistles: memory buttons that adjusts the seats and mirrors for each of us when it's pushed; a computer under the speedometer that can tell you how long you've been driving, how far you've gone, how many miles till you run out of gas, what your current gas mileage is, and the sex of your unborn child.

It looks a little stodgy and old-fashioned, though, and parking it in the city has covered it with scrapes and dings, so for the past year I've found myself looking at other cars. I'll be driving the Passat down Hands Creek Road and a brand-new Subaru Outback or Acura RDX comes sailing past, and I'll be filled with carlust. And here's the thing: I feel guilty. As if I were married to the Passat but surreptitiously checking out younger, hotter women. Shopping for a trophy wife. I know what you Freudians are thinking: that this is really about Nancy, not the car. That's utter bullshit. I look at other women all the time (they're lined up outside my office every morning) and never feel any guilt at all.

Nancy and I have gone so far as to test-drive that new Subaru, and in many ways it's terrific: roomier, better gas mileage, more ground clearance (we got stuck in our own parking area in January when the snow was over the Passat's bumper), and a jaunty style. But will I be happy with the 4-cylinder engine, which is a little buzzy and doesn't have quite enough oomph? Will I be able to adjust the front seat to cradle me in the manner to which I've become accustomed? And do I want to nick the piggy bank to the tune of $30K+ when I might get a year or two more out of the Passat?

Old Faithful Young Honey

I stay up nights worrying about these questions. It feels like a life-altering decision, though it never has before; we've bought six new cars in the past 25 years, and nary a panic attack have I had. Maybe my OCD is kicking in. The salesman at Riverhead Subaru calls every couple of days, and I keep putting him off with lame excuses. Someone, please, tell me what to do!

And yet . . . it runs like a dream. It's totally comfortable; in fact, I bought it because its driver's seat had so many possible configurations that I no longer have to stop, get out and stretch after an hour at the wheel. It has all-wheel drive, a necessity in the winter for our long, steep driveway, but it still gets 26 mpg on the highway, and its 6-cylinder engine, coupled to an automatic transition with manual passing gear, is smooth, quiet and powerful. And I love its bells and whistles: memory buttons that adjusts the seats and mirrors for each of us when it's pushed; a computer under the speedometer that can tell you how long you've been driving, how far you've gone, how many miles till you run out of gas, what your current gas mileage is, and the sex of your unborn child.

It looks a little stodgy and old-fashioned, though, and parking it in the city has covered it with scrapes and dings, so for the past year I've found myself looking at other cars. I'll be driving the Passat down Hands Creek Road and a brand-new Subaru Outback or Acura RDX comes sailing past, and I'll be filled with carlust. And here's the thing: I feel guilty. As if I were married to the Passat but surreptitiously checking out younger, hotter women. Shopping for a trophy wife. I know what you Freudians are thinking: that this is really about Nancy, not the car. That's utter bullshit. I look at other women all the time (they're lined up outside my office every morning) and never feel any guilt at all.

Nancy and I have gone so far as to test-drive that new Subaru, and in many ways it's terrific: roomier, better gas mileage, more ground clearance (we got stuck in our own parking area in January when the snow was over the Passat's bumper), and a jaunty style. But will I be happy with the 4-cylinder engine, which is a little buzzy and doesn't have quite enough oomph? Will I be able to adjust the front seat to cradle me in the manner to which I've become accustomed? And do I want to nick the piggy bank to the tune of $30K+ when I might get a year or two more out of the Passat?

Old Faithful Young Honey

I stay up nights worrying about these questions. It feels like a life-altering decision, though it never has before; we've bought six new cars in the past 25 years, and nary a panic attack have I had. Maybe my OCD is kicking in. The salesman at Riverhead Subaru calls every couple of days, and I keep putting him off with lame excuses. Someone, please, tell me what to do!

NARRISHKEIT

“Narrishkeit” means “foolishness” Yiddish (from the German “narr,” as in “narrenschiffe,” ship of fools) – not quite “folly,” like investing with Madoff, but more the kind of idiosyncratic nuttiness of which everybody has a few choice examples. One that Nancy and I share is the way we play Scrabble.

From the beginnings of our relationship (back in what I think of as the early modern era), we’ve both enjoyed games, but there’s always been a problem. When we were engaged, I tried to learn bridge, which Nancy had played in college; we had another couple as partners, a tyro and an old hand, and the whole thing was a disaster. I’m a terrible card player and couldn't learn the game, and the other couple broke up over the acrimony and general fecklessness it engendered in them. Nancy and I tried chess, but she was carrying around a lot of emotional baggage: her father was the senior champion of the state of Michigan, who delighted in thumping his eldest daughter, and playing with me brought those repressed memories back with a vengeance. Whatever we tried, ego intruded and bruised feelings ensued – except when we played Boggle with Danielle who, from the age of 17, has kicked both our butts every time. (Not because of her enormous vocabulary; more because a big part of the game involves spatial relations, seeing various combinations, at which she excels).

But lately, Nancy and I have been playing Scrabble. Well, not Scrabble – a variant called Lexulous, which is offered on Facebook. The difference is that there are eight letters instead of seven and – most important – no challenges; if you make a word that’s not in the game’s “dictionary” (I use the term derisively and loosely), it doesn’t accept it and you can recant and make another word.

Where does the foolishness come in? We could easily set up the Scrabble board and play face to face, but it works better for us to play online. So Nancy sits downstairs in the living room on her Powerbook and I sit at my desk upstairs on my iMac, and when one of us has moved, he or she shouts, “OKAY!” Talk about the machines turning us into machines! But because there’s no eye-contact, no audible grumbling, no muttered imprecations, there are no hard feelings. And we’re about equal in skill, so games are usually decided by who gets the good letters – the right combination of high-powered consonants and vowels.

What’s next? Computer tennis? Virtual sex? Stay tuned.

Saturday, February 5, 2011

CHILLY SCENES OF WINTER

I love living in East Hampton -- or at least I did until this winter. In the 30 years since we bought our first house, there have been snowfalls, some of them major, but nothing like what's been happening here. In the past month, we've been plowed twice, and still, when we arrived on Wednesday night (after a 45-minute dig-out from our parking space in the city), we got stuck at the top of our driveway and had to call AAA the next morning. The freezing rain is worse than the snow; first it melts the surface of what's already there (the base is almost two feet thick); then it turns to slush. It's like

Groundhog Day -- nine storms in five weeks, dig out and watch the new snow obliterate your everything you've just finished clearing.

When we bought our house, we never gave a thought to the fact that our driveway was 100 feet long and at a fairly steep angle. For that past two months, that's been the central fact of our lives; all our travel decisions are based on it.

For the first time, I'm considering Plan B: quit teaching and spend the winters in a warm, sunny clime. We'll give the Northeast one more winter, but if it's anything like this one, very possibly, we're outta here.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

WHAT WERE THEY THINKING OF?

MAXIM. I MEAN MAX. OR IS IT MAXINE?

King Lear’s eldest daughter, Goneril, seeks his death. Of course, so does Regan, Daughter #2, but I can better understand Goneril’s point of view. What were the monarch and his queen thinking when they named their first-born after a venereal disease? (Yes, the word was current as far back as 1547.)

I’m attuned to this topic because I don’t particularly care for my own name. I think the two rhyming syllables – Richard Horwich – sit awkwardly on the tongue and in the ear. Nothing to be done about "Horwich," which I heard a lot about when I was in school: "I love to go to Dick's house because of the whore which is there." And there's that other problem, but of course, how were my parents to know that “Dick” would acquire its present colloquial meaning, obliterating its history as simply a name to the point where, when I wrote to one of my editors, his magazine's e-mail filter would send my messages to the Trash unless I signed them “Diq.” My Aussie friend with genteel sensibilities changed it to Ricky (another bad choice). For the first ten years of my life my parents called me Dickie, which I hated, and which I still hear sometimes from people Who Knew Me When -- though that has a kind of charm. My friends the Dicksteins told me several years ago that their daughter thought one of the benefits of marrying was that it would free her from their family name. She got her wish.

My daughter Danielle will, on or about March 12th, deliver into the world a baby girl whose name will be . . . nobody knows, and the expectant parents have gone from telling me it’s none of my business to asking for suggestions. Anything in Shakespeare? I mentioned to her that the Bard had a fondness for dactylic female names, so that she could, belatedly join that '90s fad that spawned an illegitimate verse form known as the Double Dactyl; the kid could be Perdita Bellenoue, Beatrice Bellenoue, Rosalind Bellenoue, Viola Bellenoue, Cressida Bellenoue, Helena Bellenoue (but not, of course, Goneril Bellenoue) -- though double dactyls or anything rhetorically doubled, for that matter, smacks of gimmickry. They’re naming a person after all, not looking for a catchy book title. They called their now-three-year-old son "Maxim," partly because my son-in-law is French, and, oddly, because he and Danielle were under the impression that “Maxim” couldn’t be shortened to a nickname (they don’t like nicknames). If they ever move back to the States, they’ll find out how wrong they were. When he’s here on visits, people either mispronounce the French "Maxim" as the English "maxim" or just resort to the inevitable and to my mind perfectly OK “Max.” (Hey, if they name the little girl Minerva, their kids could be Max and Min – isn’t that cute?) Almost as cute as the scholar Sacvan Berkovitch being named for two executed anarchists, or the lawyer I met in Grand Rapids whose mother had been reading Gone With the Wind while she was pregnant and who has gone through life with “Rhett Pinsky” on his business card.

What prompts this reflection on parental naming sins is that there’s a girl on the roster of my Spring course with what at first seems a perfectly serviceable name, which I'll disguise except for the initials – let’s call her Andrea S. Smith. I guess her Mom never envisioned that monogram on the towels. NYU assigns e-mail addresses to its students by the following algorithm: initials of first, middle and last names followed by a number. So this kid is stuck with ass000@nyu.edu. What must high school have been like for her?

There are a lot of ways for parents to screw up children. Conferring a name that you haven’t tested out loud, or thought much about, or is appropriate to a toddler but terrible for an adult, is such an easy way to do it, I’m surprised it doesn’t happen even more often.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

LAW-ABIDING CRIMINALS

Representative Mike Pence of Indiana was quoted in the Times ("A Clamor for Gun Limits, but Few Expect Real Changes" by Adam Nagourney and Jennifer Steinhauer) as asserting, “I maintain that firearms in the hands of law-abiding citizens makes communities safer, not less safe.” That’s what the NRA keeps telling us. But "law abiding citizens" is not a fixed and stable category. Jared Loughner was a law-abiding citizen (albeit a troubled one) who had never committed a felony until he bought a pistol and shot a Congresswoman and a score of bystanders. In Mike Pence's version of a perfect world, the victims in Tucson would have protected themselves by unholstering their own weapons and executed Lougner summarily. But none of them was armed. The vast majority of Americans reject, in principle and in practice, vigilante justice.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)